Someone is on the plane

that noses 2,000 feet into the air, stops,

then drops. Someone is in

the tornado-flattened Texaco station.

Someone is on the bus the suicidal

or stroke-struck driver launches

through the guardrail and off the mountain.

It isn’t you. You’re watching

a ticker scroll placidly across

the bottom of the screen, thinking

awful, awful, and below those words,

deeper than articulation can go,

hums your golden gratitude

that once again this is a tragedy

you can witness but not touch.

You can continue the work

of chewing your waffle. You can

approach the smoothed edges

of disaster, and you can,

when you light on a rough spot—

the image of the little boy’s

brown shoe in the rubble, the woman

who looks like your mother

howling in a blue hat—pull back.

Some will say this is cowardice,

your unwillingness to hold

these horrors in your hands. But

if you considered, truly, the dead child,

the husband that the woman

who looks like your mother

will never see again; if you considered,

truly, what it means that a plane

could drop without warning

with its full load of daughters

and coaches and magazine-readers,

that the sky might unfold a beast

that will hunt you without reason,

that the white-mustached man

behind the wheel of your bus

is not programmed but is a human

stranger you have chosen to trust

with your absurdly flimsy life—

how in the world could you do

the work of chewing your waffle?

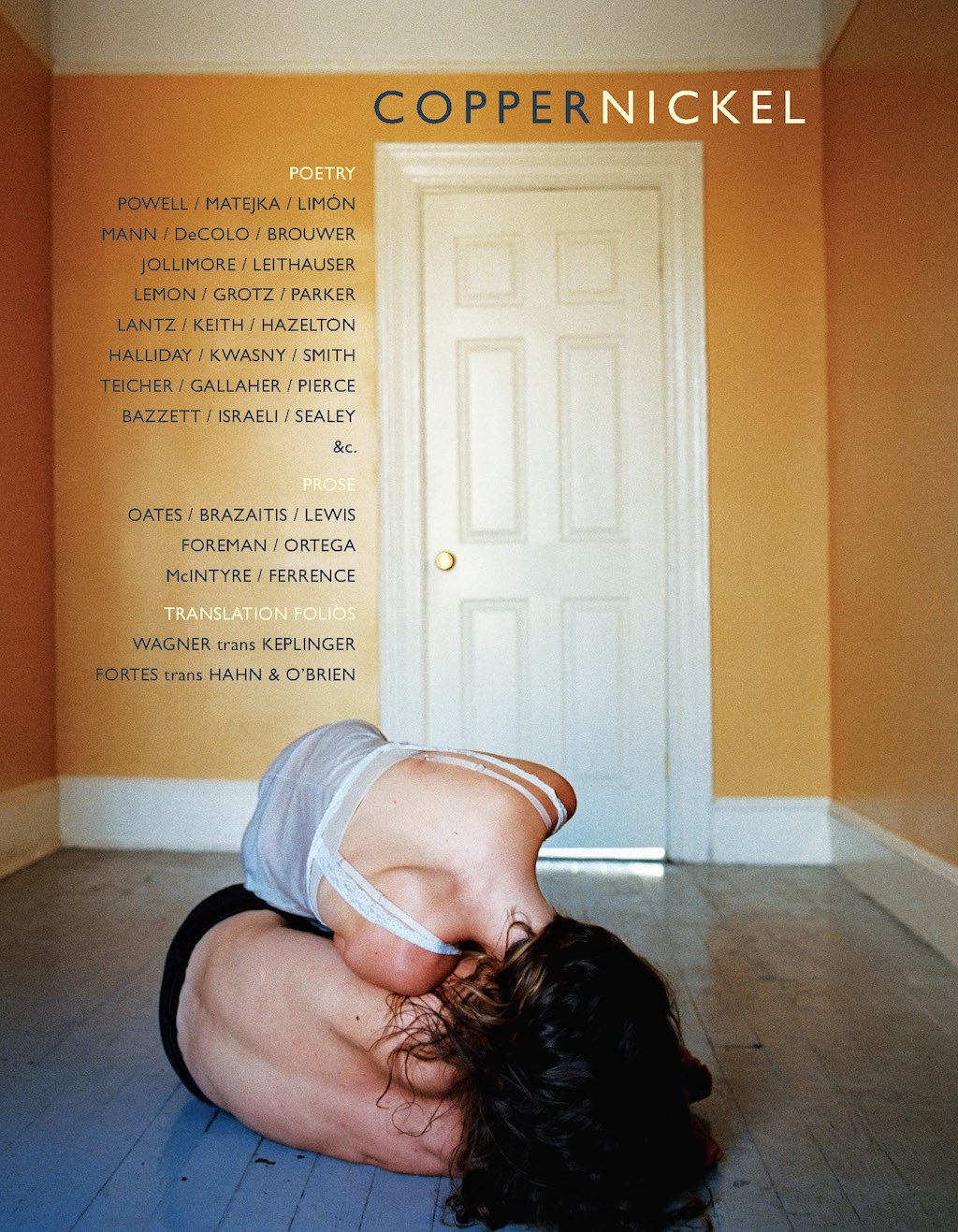

How could you do the impossible work

of putting your child to bed,

saying goodnight, closing the door

on the darkness?